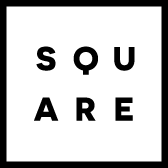

The year was approximately 2013. A young girl with a very ill-advised haircut takes to the stage in The Egg Theatre in Bath, and performs two poems: ‘Tichborne’s Elegy’ (Chidiock Tichborne, 1586) and ‘God, A Poem’ (James Fenton, 1983). She narrowly misses out on the win to a peer who inconceivably also performs ‘Tichborne’s Elegy’. Besides being quite the sore loser, the girl goes home and a decade passes (albeit with significantly improved rote memory and public speaking skills). One night at The Square Club in 2023, this girl, now a woman, bumps into the very people behind this competition, who just so happen to be members.

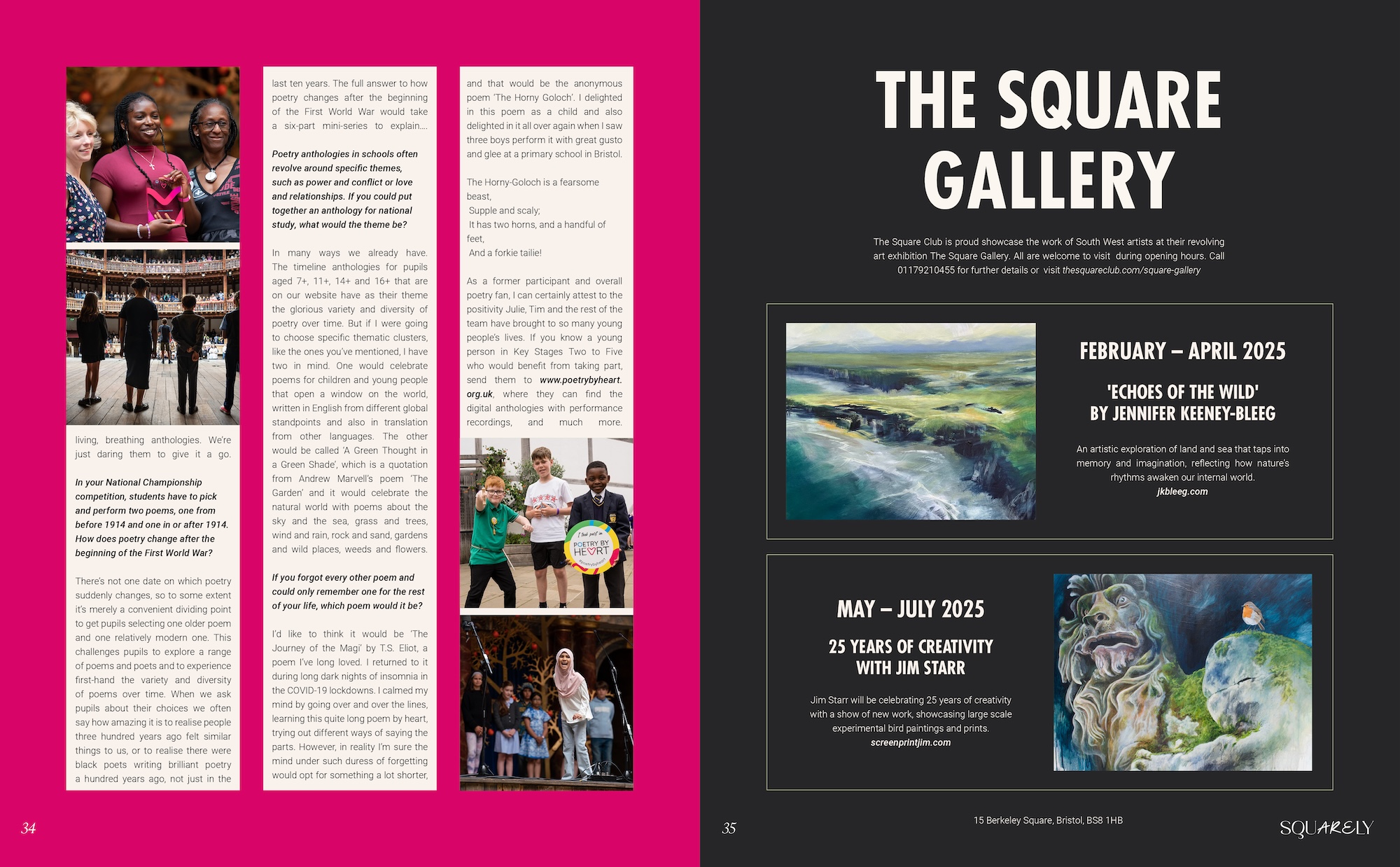

You may have guessed, dear reader, that this girl is I, Evelyn Andrews. I am but one of 200,000 young people who have competed in the Poetry By Heart competition across the UK. Poetry By Heart encourages young people of all backgrounds to learn a poem and perform it out loud, establishing a lifelong love for poetry. Founded in 2012 by educator Dr Julie Blake and poet Sir Andrew Motion, the competition has gone from strength to strength, with Julie and fellow co-director Dr Tim Shortis recently in the 2025 New Year’s Honours List (read more on page X).

As our most recent Local Heroes (national, really), I asked Julie some questions about their important work bolstering poetry in schools.

In challenging economic climates, school curriculums often prioritise STEM subjects to respond to rising demands in the workforce, encouraging students down paths that may lead them away from the study of humanities, and consequently, poetry. Why is it important to keep poetry alive in schools and further education?

The Booker prize-winning novelist and poet Margaret Atwood has my favourite answer to this question, and one we’ve had in different forms from many of the amazing poets we work with. She says, “Every culture we know has some form of poetry. Poetry matters to us as human beings because it is deeply engraved in our DNA.” To that I’d add what the 18th century writer, poet and dictionary-maker Dr Samuel Johnson said, “The only end of writing is to enable readers better to enjoy life or better to endure it.” Whether you’re going to train to be a nuclear scientist, a software developer, a civil engineer or a doctor, we are all human beings with poetry hardwired in our DNA, and we will all need to find ways to enjoy and endure our lives, especially when storm clouds are brewing on the horizon. Why would we not include it in schooling?

What is it about poetry that transcends the boundaries and differences in the various student backgrounds that you work with? How does poetry enable accessibility in schools?

If you accept that poetry is part of our human DNA, then it follows that it must have the capacity to reach everybody. The evidence from thousands of teachers working with us for thirteen years corroborates this. In our annual survey, we ask teachers to tell us about something that has surprised or delighted them about taking part, and we have heard countless stories about pupils overcoming memory difficulties and stammers, pupils with limited conventional literacy feeling able to participate through spoken performance, and at our very first pilot session in Bristol fourteen years ago we witnessed a teacher’s jaw drop as a pupil who had never spoken in her class before stood up, pushed back her hoodie and clear as a bell, recited Lord Byron’s poem ‘The Destruction of Sennacherib’. Poetry finds us where we are and offers us a channel to say something funny, sad, beautiful, mysterious or mad, whatever we find there that reverberates in us and helps us to give voice to.

What would you say is more important, the performance aspect of the competition, or the preservation of poetry for the upcoming generation?

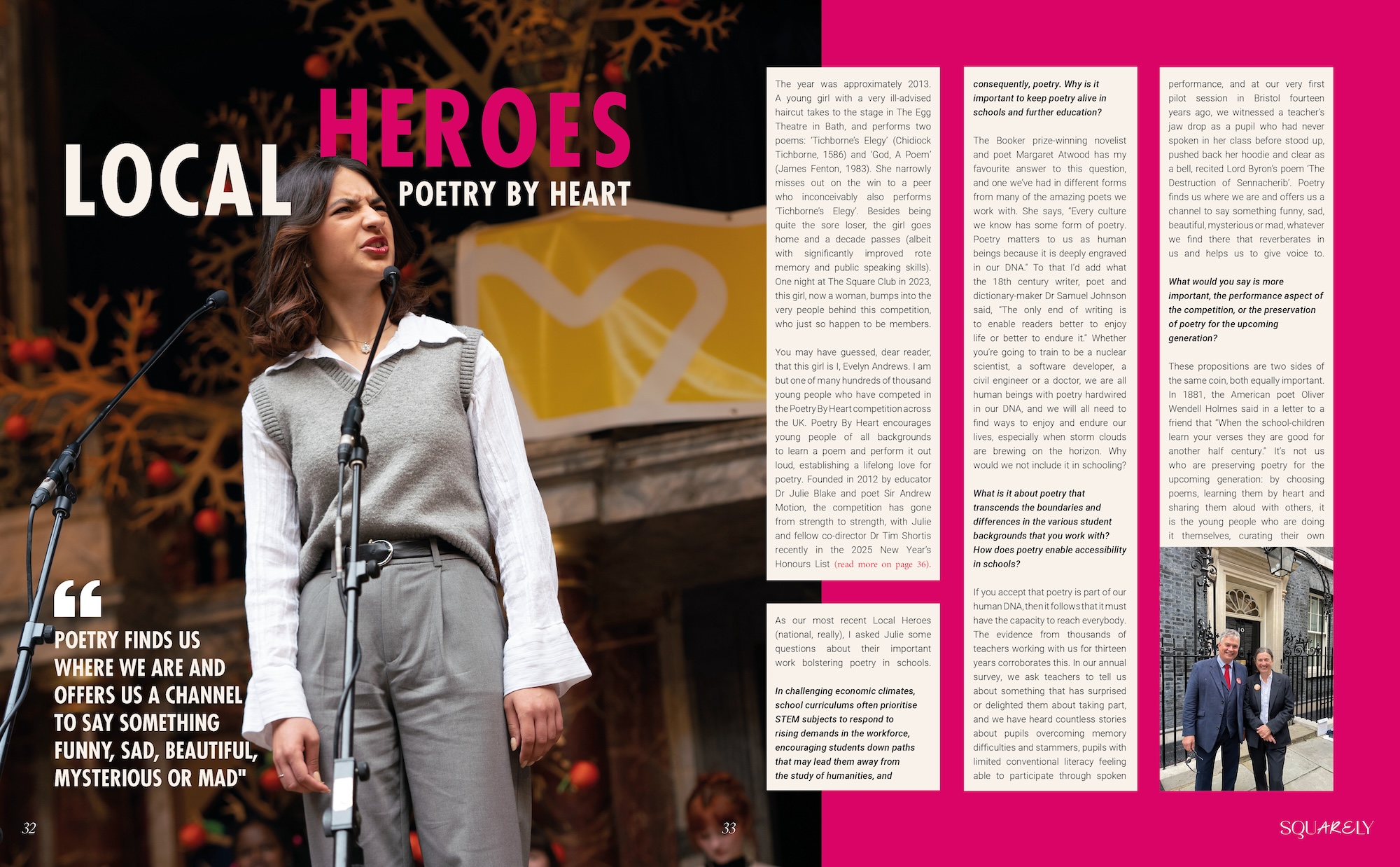

These propositions are two sides of the same coin, both equally important. In 1881, the American poet Oliver Wendell Holmes said in a letter to a friend that “When the school-children learn your verses they are good for another half century”. It’s not us who are preserving poetry for the upcoming generation: by choosing poems, learning them by heart and sharing them aloud with others, it is the young people who are doing it themselves, curating their own living, breathing anthologies. We’re just daring them to give it a go.

In your National Championship competition, students have to pick and perform two poems, one from before 1914 and one in or after 1914. How does poetry change after the beginning of the First World War?

There’s not one date on which poetry suddenly changes, so to some extent it’s merely a convenient dividing point to get pupils selecting one older poem and one relatively modern one. This challenges pupils to explore a range of poems and poets and to experience first-hand the variety and diversity of poems over time. When we ask pupils about their choices we often say how amazing it is to realise people three hundred years ago felt similar things to us, or to realise there were black poets writing brilliant poetry a hundred years ago, not just in the last ten years. The full answer to how poetry changes after the beginning of the First World War would take a six-part mini-series to explain….

Poetry anthologies in schools often revolve around specific themes, such as power and conflict or love and relationships. If you could put together an anthology for national study, what would the theme be?

In many ways we already have. The timeline anthologies for pupils aged 7+, 11+, 14+ and 16+ that are on our website have as their theme the glorious variety and diversity of poetry over time. But if I were going to choose specific thematic clusters, like the ones you’ve mentioned, I have two in mind. One would celebrate poems for children and young people that open a window on the world, written in English from different global standpoints and also in translation from other languages. The other would be called ‘A Green Thought in a Green Shade’, which is a quotation from Andrew Marvell’s poem ‘The Garden’ and it would celebrate the natural world with poems about the sky and the sea, grass and trees, wind and rain, rock and sand, gardens and wild places, weeds and flowers.

If you forgot every other poem and could only remember one for the rest of your life, which poem would it be?

I’d like to think it would be ‘The Journey of the Magi’ by T.S. Eliot, a poem I’ve long loved. I returned to it during long dark nights of insomnia in the COVID-19 lockdowns. I calmed my mind by going over and over the lines, learning this quite long poem by heart, trying out different ways of saying the parts. However, in reality I’m sure the mind under such duress of forgetting would opt for something a lot shorter, and that would be the anonymous poem ‘The Horny Goloch’. I delighted in this poem as a child and also delighted in it all over again when I saw three boys perform it with great gusto and glee at a primary school in Bristol.

The Horny-Goloch is a fearsome beast,

Supple and scaly;

It has two horns, and a handful of feet,

And a forkie tailie!

As a former participant and overall poetry fan, I can certainly attest to the positivity Julie, Tim and the rest of the team have brought to so many young people’s lives. If you know a young person in Key Stages Two to Five who would benefit from taking part, or know of a school that is not currently taking part in the competition, send them to www.poetrybyheart.org.uk.